1962 World Cup poster, designed by Galvarino Ponce, Publisher / Commissioning Body: FIFA / World Cup Organizing Committee

This article is part of a series discussing the history and evolution of the FIFA World Cup.

“Porque no tenemos nada, queremos hacerlo todo” (“Because we have nothing, we want to do it all”). These were the passionate words from Carlos Dittborn, the head of the Chilean delegation during his presentation to FIFA as one of the two countries bidding to host the 1962 World Cup tournament, on June 10th, 1956. Argentina, the other country bidding for the competition, had finished its presentation earlier in the day and had bragged “We can do the World Cup tomorrow. We have everything.” The final vote was 31 votes for Chile, 12 for Argentina, and 13 abstentions.

His words would turn out to be tragically prophetic. Qualifying started on August 21st, 1960. Three months earlier, on May 22nd, 1960, Chile was struck by one of the most devastating earthquakes and the strongest the world had ever seen. At 9.5 magnitude and lasting 10 minutes (no other earthquake has ever lasted that long on a continuous basis) it killed approximately 6,000 people and severely damaged or almost destroyed several of the cities that had been selected as hosts. European nations started lobbying to move the World Cup (there was still a certain entitlement on the part of Europe that their continent should continue hosting these events). However, FIFA strongly rejected any such attempts and Chile would go on to host what is considered one of the best organized World Cups.

Carlos Dittborn would not live to see his outstanding work come to fruition. A month before the inauguration he died from a fatal heart attack at age 41. It was said that the combination of his untiring efforts to land the event in Chile, his total commitment to planning the World Cup, and a severe disagreement with two Chilean sports organizations who had demanded hundreds of free tickets to the World Cup (which Dittborn refused), were the main cause of his tragic death.

Qualifying

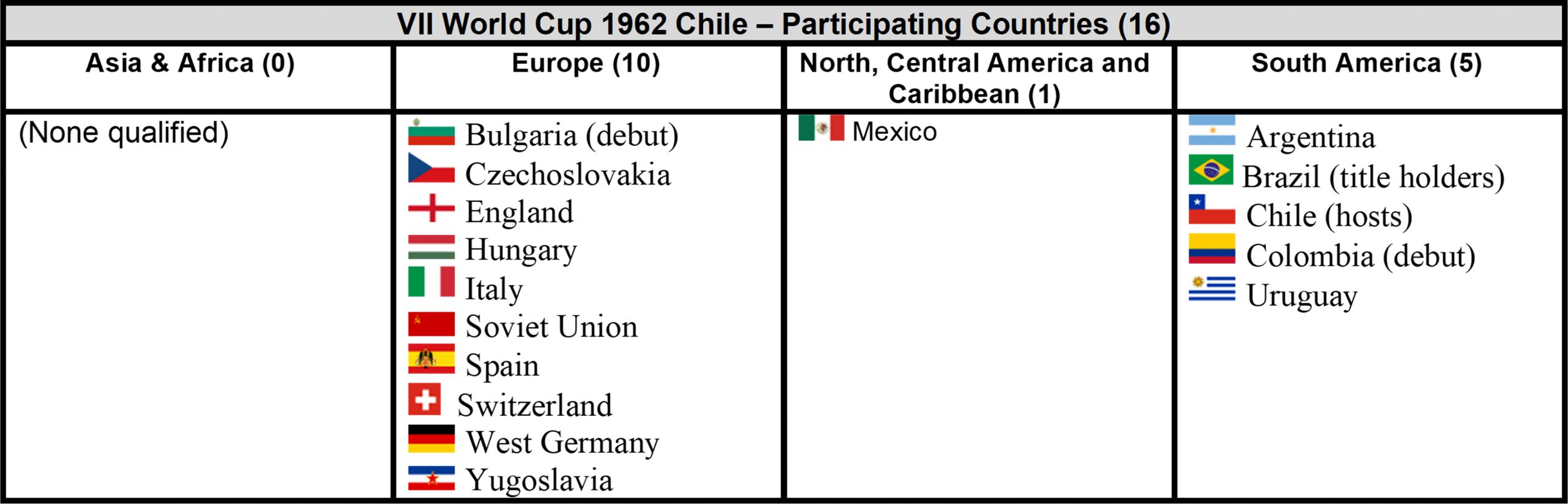

African and Asian nations would participate in the qualification round but only teams from Europe and the Americas would wind up competing in this World Cup. FIFA was again tilting the playing field in favor of European teams and as such designed qualifying to make it extremely challenging for teams from Africa, Asia, North America (Canada, USA, and Mexico), and the Caribbean. Teams from those countries had to play extra qualifying games against European teams (in the case of Africa and Asia) and South American teams (in the case of North America and the Caribbean). No African nation would reach the final tournament until 1970 when FIFA finally gave the Confederation of African Football (CAF) one guaranteed place.

A total of 56 teams entered the 1962 FIFA World Cup qualification rounds, competing for the 16 spots in the final tournament. Chile, as the hosts, and Brazil, as the defending champions, qualified automatically, leaving 14 spots open for competition.

The 16 spots available in the 1962 World Cup would be distributed among the continental zones as follows:

- Europe (UEFA): eight direct places plus two spots in the Intercontinental Playoffs (against teams from Asia and Africa), contested by 30 teams (including Israel and Ethiopia).

- South America (CONMEBOL): five direct places plus one spot in the Intercontinental Playoffs (against a team from North America or the Caribbean), with two direct qualifying teams (Chile as the host and Brazil as the defending champions). The other three spots were contested by seven teams.

- North, Central America and Caribbean (CCCF/NAFC): one spot in the Intercontinental Playoffs (against a team from CONMEBOL), contested by eight teams.

- Africa (CAF): one spot in the Intercontinental Play-offs (against a team from UEFA), contested by six teams.

- Asia (AFC): one spot in the Intercontinental Play-offs (against a team from UEFA), contested by three teams.

The soccer federations from Asia, Africa, Caribbean, and North America strongly protested FIFA’s decision to make them play additional games against Europe and South America but their criticism fell on deaf ears. Despite the longer road, one team from North America did manage to qualify. After a marathon set of fixtures, Mexico won their playoff games against Paraguay, tying the first game and winning the second.

Teams still earned two points for a win, one for a tie, and zero for a loss. If at the end of qualifying, teams were tied in points within their qualifying groups, then an extra playoff game was required. If there was no winner in that playoff game, then the winner would be decided by drawing lots.

Four teams required an extra playoff game: Bulgaria, France, Sweden, and Switzerland. The winners were Bulgaria and Switzerland, which resulted in the second and third place teams from the previous World Cup being eliminated.

The following 16 teams qualified for the 1958 World Cup tournament:

1962 World Cup Participants, table done by Jose F Guerra

1962 World Cup Participants, table done by Jose F Guerra

The Tournament

Because of the devastation from the 1960 earthquake, only four venues were capable of holding the event. And even then, three of them had capacity of less than 20,000 spectators. One of those stadiums was renamed the Estadio Carlos Dittborn in honor of the individual that won the bid and organized the tournament.

The sixteen team were placed in four groups of four with the same round-robin format used in the previous World Cup. Goal average would be used to determine tie breakers at the end of group play if teams were tied in points. If teams were still tied in points and goal average, then lots would be drawn as the tie breaker. This is how the teams were groups, showing the top two teams (shaded in green) that advanced to the knockout stages.

*England advanced due to better goal average than Argentina.

The 1962 tournament, while extremely well organized, is considered one of the poorest in terms of quality of play and openness (even though the 1990 World Cup was the lowest scoring tournament in the history of the men’s event). Defensive structures were starting to take over. Rough, physical, and even violent play became more frequent. Even so, there were games that to this day are considered among the best ever played.

In Group 1 there were epic games which saw Colombia, debuting in the World Cup, come back from behind the Soviets 0-3 and ending up tying the game 4-4, with the Soviets desperate for the game to end. The same Soviet Union would suffer a serious injury to one of its players, defender Eduard Dubinski, who suffered a broken leg after a collision with Yugoslav forward Muhamed Mujić. The incident was so blatant that the Yugoslav delegation sent Mujić home and he didn’t play another game for the Yugoslav team during the rest of his professional career. Dubinski tragically died of this injury a few years later.

Group 2 saw one of the most violent games ever in the history of the tournament. Italian journalists had written very negative things about Chile before the World Cup. Chileans were naturally incensed and that fury spilled onto the national team. The match between Chile and Italy is now known as “la Batalla de Santiago” (the battle of Santiago) since it was held in the city of Santiago in front of over 66,000 spectators. Two Italian players were expelled, and the match saw repeated attempts from players on both sides to harm their opponents. Despite Chile winning 2-0, the Italian team still needed police protection to leave the pitch and the stadium safely.

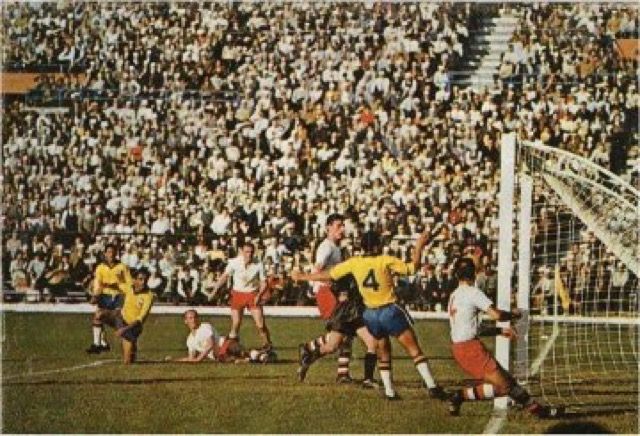

Group 3 was the least marred by violence. Pelé had again started for Brazil but only played one full game (the first one against Mexico) where he was instrumental in guiding his team to victory 2-0. But in the second game against Czechoslovakia, he injured his leg and didn’t play for the rest of the tournament. This particular match ended in a 0-0 draw. However, by all accounts, the match was considered one of the best in the tournament because of the high technical and tactical skills shown by both teams, the near‑misses from both sides, strong individual duels, and constant momentum shifts. The two teams would meet again in the final.

Group 4 was a mixed bag, with Hungary having one of its last strong performances in World Cup play and England advancing to the knockout stages after ending above Argentina in the standings due to better goal average. Argentina’s game against England in group play would become the beginning of a bitter rivalry which would culminate in the 1986 World Cup quarterfinals.

The knockout stages saw several thrilling games with several surprises. Chile knocked out the Soviets who were the defending European Champions and went to the semi-final where they fell to Brazil in a thrilling 4-2 match. Brazil had already beaten England 3-1 when they beat Chile to reach the final. Czechoslovakia, whom the pundits gave no chance of winning anything in the tournament, beat Hungary and Yugoslavia to reach the final.

Among the firsts in this tournament were:

- First to use goal average as the official group tiebreaker (instead of playoff replays)

- First in which the tournament’s goals-per-game average fell below 3 (2.78 goals per match)

- First where no playoff matches were required for teams tied in points

- First attendance for Colombia and Bulgaria

- First and only Olympic goal (direct from corner kick) ever scored at a men’s World Cup, by Marcos Coll

- First and only time six players shared top‑scorer honors at a World Cup (Garrincha, Vavá, Leonel Sánchez, Flórián Albert, Valentin Ivanov, Dražan and Jerković, with four goals each)

- First and only time Chile ended in the top three

Relevant Players

- Garrincha (Brazil) – Brazil’s star right winger stepped up after Pelé was injured in their second game and took over, dominating matches and finishing as one of the joint top scorers (four goals)

- Leonel Sánchez (Chile) – The host nation’s standout player, a left winger, Sánchez scored 4 goals (joint top scorer), delivered crucial assists, and helped Chile achieve a historic third‑place finish.

- Flórián Albert (Hungary) – The team’s young sensation who also scored four goals (joint top scorer), showcasing technical ability and maturity beyond his age

- Valentin Ivanov (Soviet Union) – The Soviet midfielder and another joint top scorer with four goals, he played a major role in advancing the team from a tough group

- Dražan Jerković (Yugoslavia) – The Yugoslav striker finished with four goals led attack as his team reached the semifinals and ultimately placed fourth.

The Final

The defending champions, Brazil had again reached the final with their fluid and dazzling individualities such as Garrincha, Vavá, Amarildo (who had replaced Pelé), Zito, Didí, among others. Czechoslovakia had surprised everyone in reaching the final with more tactical and teamwork discipline than individual play. Their focus on disciplined defensive structure, compact shape and patience out of possession, counter‑attacking transitions, sharp, opportunistic finishing, and strong goalkeeping enabled them to get past more favored teams such as Spain, Hungary, and Yugoslavia.

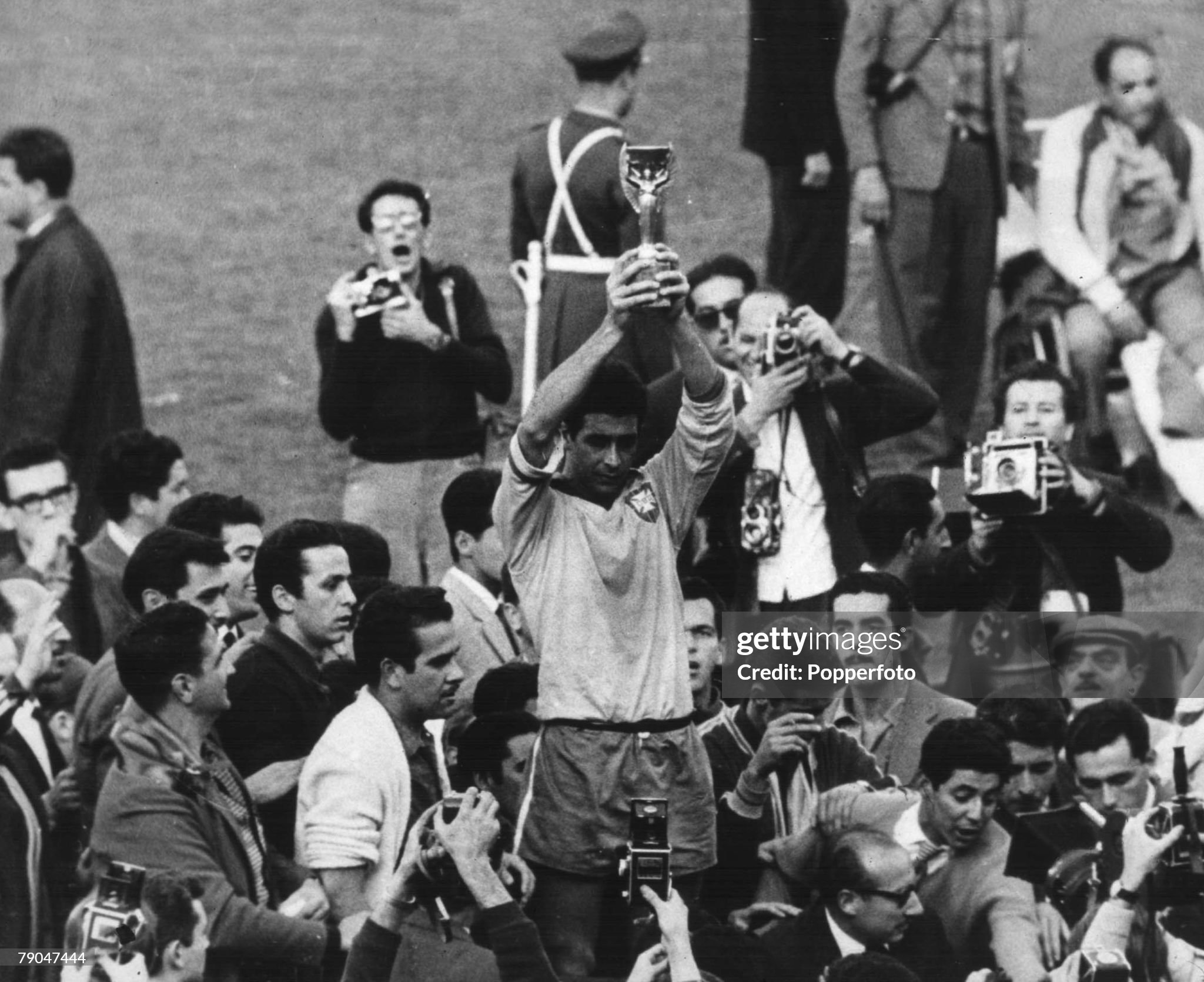

And they again surprised when they went ahead 15 minutes into the game with a brilliant team play that built from their backfield, surprising the Brazilian backline and their goalkeeper with their fast pace in the final third. But the Czech joy wouldn’t last long. Brazil equalized two minutes later with a brilliant individual play by Amarildo and the score stayed 1-1 going into halftime. In the second half Brazil increased the pressure on their opponents, constantly attacking, putting on a display of their individual skills, and scoring twice to secure their second championship in a row, 3-1.

Two contrasting styles were on display during this final: the individual brilliance and fluid game of the Brazilians that now became known as “O jogo bonito” (the beautiful game) against the disciplined but effective tactical play of Czechoslovakia.

The whimsical made its appearance again during the tournament:

- During the semi-final between Chile and Brazil, a Chilean player was sent off when he said something to the central referee, Arturo Yamasaki, because he thought he didn’t speak Spanish. Yamasaki was born in Peru of Japanese parents, so he spoke Spanish.

- When Chile was eliminated in the semi-final by Brazil, one Chilean newspaper wrote (translated from Spanish) “After having eaten Swiss cheese, Italian pasta, German sausage, and drunk Russian vodka, Chileans were not able to drink Brazilian coffee”.

- Mário Américo, Brazil’s masseur, stole the ball at the end of the game as he had done in 1958.

The game was about to take a turn that would forever change the way teams prepared for these tournaments. In the 1966 World Cup we’ll see how European teams prepared for and played the titanic games against South American teams during that competition that would be hosted by England.

Brazilian team before final against Czechoslovakia, Photographer unknown, source Associated Press.

Action during the Brazil-Czechoslovakia final in the 1962 Chile World Cup, photographer unknown, source Getty Images

World Cup Final, 1962, Santiago, Chile, Brazil 3 v Czechoslovakia 1, 17th June, 1962, Brazilian captain Mauro holds aloft the Jules Rimet trophy after his team defeated Czechoslovakia to win their second consecutive World Cup championship (Photo by Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)